The New York Times recently ran a column by Michelle Goldberg titled: “Is Claudia Sheinbaum the Anti-Trump?” This column captured my attention. The idea that there could be a female president, serving as an example of leadership polar opposite to Donald Trump, felt hopeful in a world full of governments leaning towards authoritarianism. So far in her term, she has juggled Mexico’s relationship with the United States, taken steps to mitigate crime, and created many departments, including the Ministry of Women and the Ministry of Science, Humanities, Technology, and Innovation. Sheinbaum has found ways to juggle US relations with both appeasement and standing firm. Her approval level is at a stunning 78%. By the end of that article, I was sufficiently captivated. However, as I did more research, not everything is quite as good as I had first assumed, and that was largely ignored by this New York Times article. To better understand what is going on now, it is critical to understand the past of Mexico’s government as well as Sheinbaum’s predecessor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador.

To understand this precedent, I spoke with AP Comparative Government and AP US Government teacher, Mr. Garikes. Mexico is one of the six countries that AP Comparative Government students learn about, and for a good reason. Starting with the establishment of a revolutionary government in 1934, Mexico gradually shifted conservative regime, with a dominant political party, Partido Revolucionario Institucional, or the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). PRI controlled every facet of political life: from the presidency, to the senate, to the supreme court, nearly every official was a member of this party. The PRI held control of not only the Congress of Labor, but also other labor unions and peasant unions. In the cases of any rebellions, the combination of the PRI’s long-standing political power, in addition to their connections to unions, led to no successful rebellions. However, starting in the 1970s, a political transition began, and the country shifted to the even more conservative group: Partido Acción Nacional (National Action Party or PAN). In the election in 1997, the PRI finally lost an election and PAN took power, balanced with another party, the Party of the Democratic Revolution. Nonetheless, after PAN took power, instead of moving Mexico towards a more balanced democracy, it consolidated power and did not relinquish power until 2017. This is where Claudia Sheinbaum and her predecessor, Andrés Manuel López Obrador, come in.

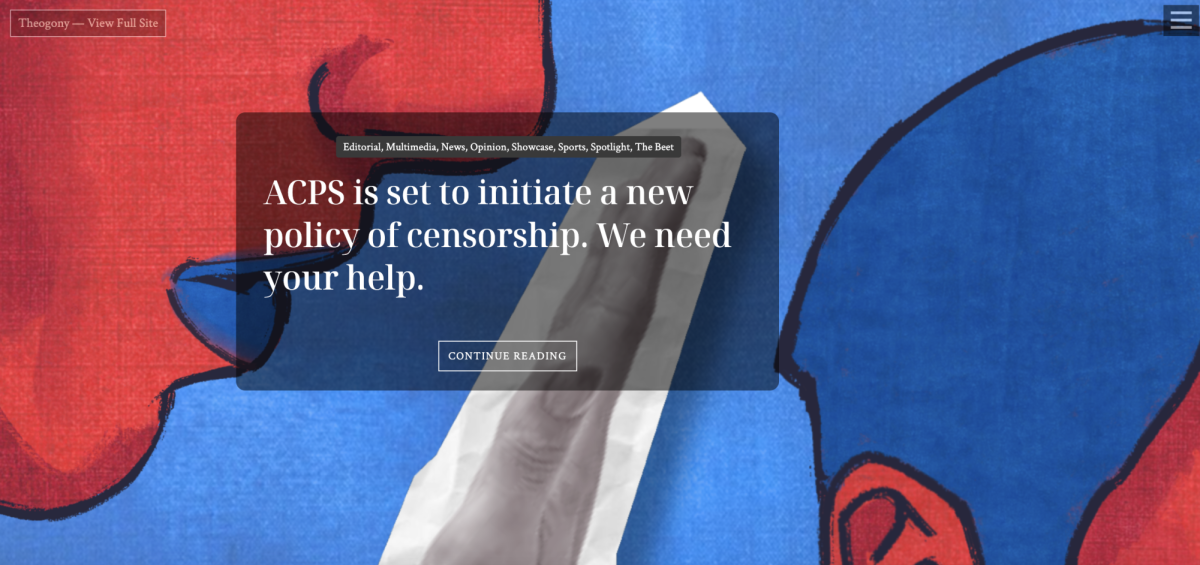

When Obrador took power, with a left-wing party, the Morena party, he, just like PAN, signaled a change in government. However, despite programs that his party presented to help the poor and mitigate cartels, he began to restrict areas of the press. Mr. Garikes commented on this, saying, “He has been very critical of the press to the point that he’s pointed to the press as his enemies — he’s released names of private numbers of members of the press. He’s… turning people against [the press].” This stands for only one of the many things that Obrador has done to consolidate his power. He also passed judicial reforms that made the Supreme Court elected by popular vote rather than appointment. While this can continue the reach of democracy, it also puts more power into the hands of the Morena party.

Sheinbaum was the chosen successor to Obrador, so while she ran for president, she was already at the helm of the Morena party. She won the election and, as you might have guessed, that brings us to today. Sheinbaum has continued many of Obrador’s policies into her administration, raising some doubts about whether she will continue this increasingly authoritarian trend or not. Thirteen of the sixteen constitutional reforms that she passed in her first few months were created by Obrador. And, while her popularity index remains high, only 30% of Mexicans approve of how she has dealt with corruption. In addition to statistics, her success, Spanish teacher Profe Gilbert, whose wife is from Mexico, says is going to come down to, “a legacy that she’s gonna continue from her predecessor who, for a lot of people, was not the best leader.”

It is difficult to reconcile the fact that this president, who at first glance seems like a balm to the world’s terrifying state, might actually be the continuation of systems with authoritarian tendencies. While this might feel out of place in a world full of right-wing authoritarian groups, articles from The Washington Post and The Atlantic raise concerns that Sheinbaum is still tightening the Morena’s party’s grip on Mexico, acting as a left-wing authoritarian. In addition to continuing Obrador’s policies, she has also begun directly confronting the press when they speak against her, as happened with Ernesto Zedillo, a former president of Mexico, who wrote an opinion piece for The New York Times. In a press conference she said, “Our political adversaries are looking for new spokespeople — Now it turns out that Zedillo is a stalwart of democracy.” Take that as you will, but it is important to keep in mind these patterns as they develop.

Instead of leaving me with answers, this has just left me with questions. What is Sheinbaum trying to do with her newfound power? How should we reconcile both the successes of Sheinbaum coupled with the impending threat of authoritarianism? I know I don’t have the answers, but I hope this has given you some context for the larger scope of implications of actions that are being taken on an international level. The threat of authoritarianism is on the rise across the globe, and understanding how these processes have occurred in other nations is critical when considering solutions to the issues that the US is undergoing.