Esperanto estas artefarita lingvo. Esperanto is an artificial language that was created in 1887 by Polish optometrist L.L. Zamenhof in hopes of bridging ethnic divides and achieving world peace. Zamenhof had been subject to bias and prejudice for most of his upbringing, hence his drive to create a worldwide language.

Zamenhof grew up in Bialystock, Poland, where most of the inhabitants were either Russian, Polish, German, or Jewish. Due to the diversity, there was an overall lack of understanding between all the ethnic groups and, consequently, conflict. Each group perceived the other as “outsiders” because they could not communicate with one another. In one of Zamenhof’s journals, he wrote,“I was brought up as an idealist; I was taught that all people were brothers, while outside in the street at every step I felt that there were no people, only Russians, Poles, Germans, Jews, and so on.”

Zamenhof undoubtedly had genuine intentions in his creation of Esperanto. That being said, many linguists critique it because trying to achieve linguistic homogeneity comes at the expense of cultural richness and nuances, which is part of the beauty of humanity. I believe that the universal use of Esperanto would never actually occur because, as long as foreign cultures exist, the extinction of languages will never happen. This is because language is so much more than just grammar or syntax; it is context, and that is ultimately something that can never be translated.

During an interview with Dr. Klein, she recounted that what initially intrigued her about Esperanto was that “it was created by a Jewish man who was so used to languages that he thought ‘if only these people could speak a common language they could understand each other’ […] there wouldn’t be any more war, hatred, or conflict.” However, like many other critiques, she believes “it’s too difficult for most people […] and you can’t make yourself understood in it.”

Madame Van Way also shared a similar opinion by saying “it’s good to know about, but I think it’s better to focus on the languages that are spoken now.”

When Zamenhof was creating Esperanto, he wanted it to be as easy to learn as possible. So, he merged Russian, French, English, German, Spanish, and other European/Western European language attributes to formulate Esperanto; however, many say that this made Esperanto easy only for those who speak an Indo-European language, which leaves out many Northern-African and South-Asian language speakers.

Esperanto consists of a 28-letter Latin alphabet. It adds six letters to the typical English alphabet, “ĉ, ĝ, ĥ, ĵ, ŝ and ŭ.” These extra diacritics are added to the sound of letters to help with the pronunciation of ambiguous or vague words. Similarly, Esperanto is an agglutinative language, which means it forms words by taking different morphemes- the smallest pieces of a word that still have grammatical meaning- that have their own meaning and pushing them together to create a new word. An example of a morpheme in Esperanto is the use of the suffix “-j,” which expresses plurality in a word. Another notable piece of Esperanto is that it only has one definite article, much like English: “la.” This is very different from many languages and also makes it a lot easier to learn.

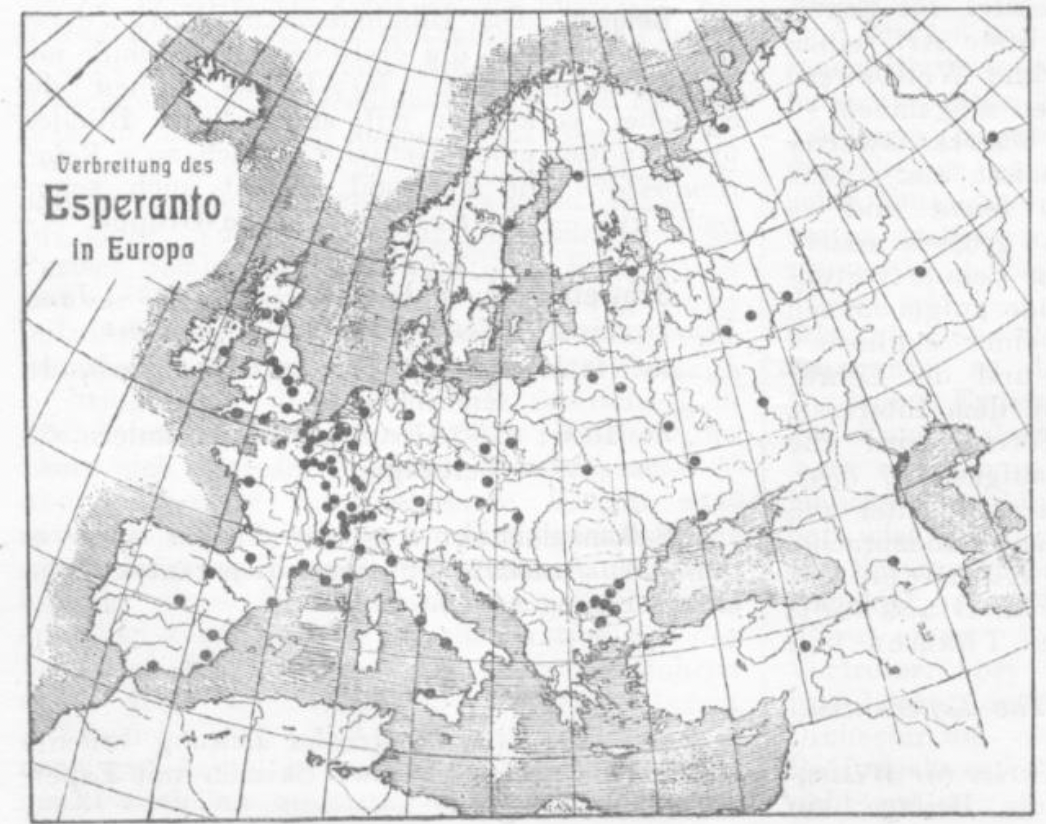

Interestingly enough, Esperanto saw its peak as the Belgian-Prussian Empire emerged from the 19th century as an industrial superpower. The language saw a large influx in speakers throughout the area, despite its small population. Regardless, the language was never formally adopted.

After World War I, Esperanto piqued the interest of many international delegates. In 1920, a Japanese representative in the League of Nations, Nitobe Inazō, proposed that the language be adopted within international schools for the use of better international cooperation. Ten delegates in the League accepted this proposal; however, only one person rejected it: Gabriel Hanotaux, a French ambassador. In fact, Hanotaux and the entire French government were so outraged by this initial proposal that they continued to reject all attempts at implementing Esperanto within foreign schools for children to learn and banned the use of Esperanto in all French schools and universities. In an excerpt from The Washington Herald, the French’s reasoning for this was that “French and English would perish and the literary standard of the world would be debased.”

My introduction to Esperanto started in 8th grade, when I first heard it mentioned by my then French teacher, Madame Walker. I then learned more about it sophomore year with Dr. Klein. Esperanto, along with other languages, continued to be something I was consistently interested in. Throughout my learning of foreign languages, such as Esperanto, I have always wondered why language is important. To me, language shapes how we connect, understand, and exist in the world, while simultaneously revealing the untranslatable essence of identity and culture. To learn a new language is to embrace a richer, more profound way of seeing and being- a way of thinking that bridges divides and deepens human connection.