Earlier this month we set out on an adventure, seeing an incredibly rare astrological event, a total solar eclipse. The last eclipse in North America was in 2017 and the next one will be in 2044. While we were hesitant to go, we were quickly convinced once thinking about this rarity. Surely one Monday of school could wait instead of us waiting 20 years more to see an eclipse. So we set off, making plans less than a week before the eclipse was scheduled to occur. At that time all of the best weather channels and cloud maps pointed us to one place on the map, Pittsburgh, PA. Right on the line of totality as the eclipse moved diagonally across the country from Texas to Vermont.

As we’d never seen an eclipse before, we were pretty optimistic about the idea. We set off on the four hour drive to Pittsburgh with no doubts in our minds, however, once settled at the hotel things took a turn. All of the cloud maps that had shone perfectly clear blue skies had turned suddenly to forecasting heavy clouds for miles around us. Translation: there was no way we were going to see the eclipse in this weather. Our hopes were pretty dashed at this point, so we went to bed feeling apprehensive and unsure about what the next day would bring us.

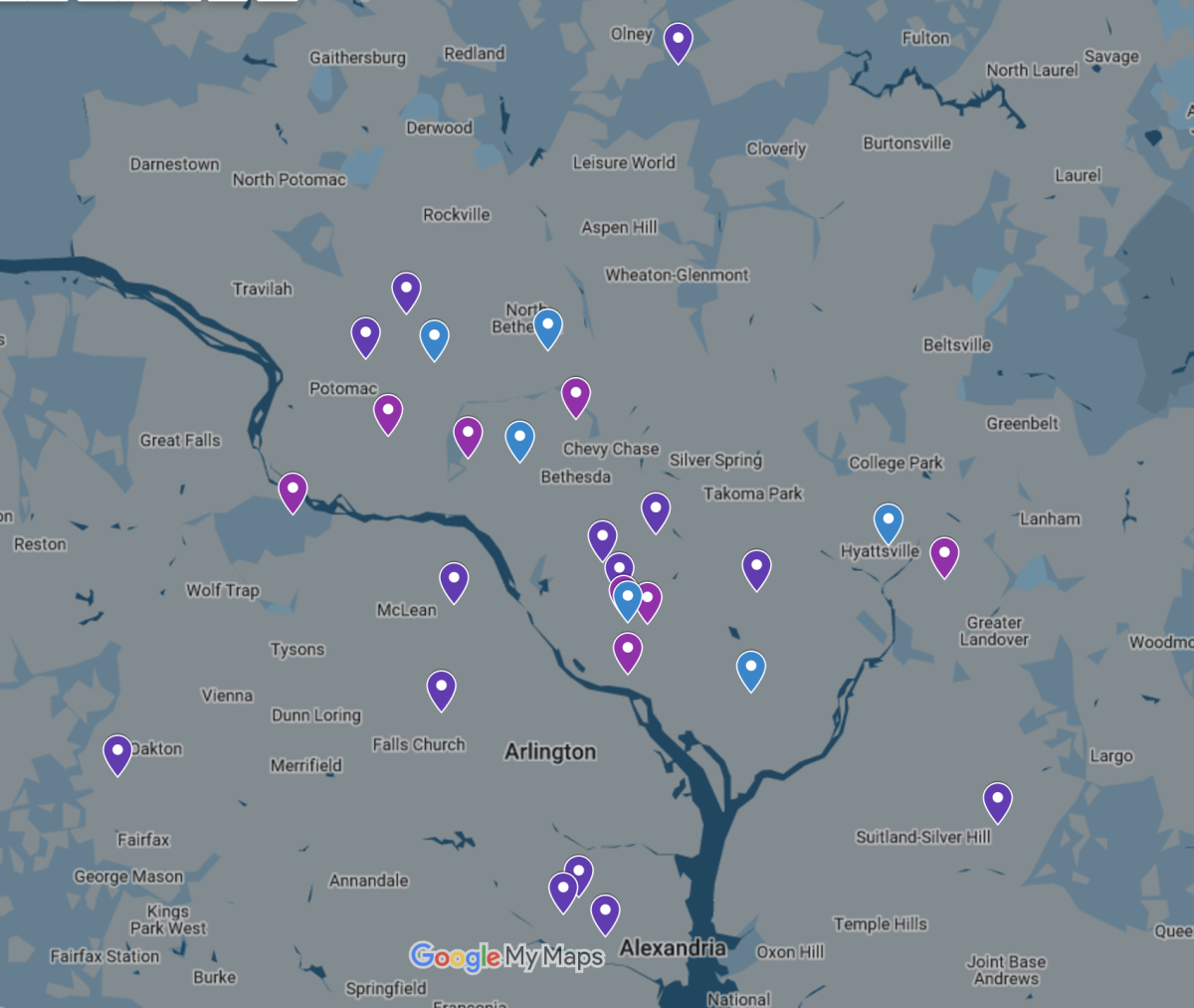

At 5 am the next morning, bad turned to worse as the cloudy forecasts turned to full on rain storms around us. We made a pretty quick decision to head West where the skies seemed to be vaguely clearer, although cloud coverage was still showing around 60-80%, but it was better than our current 80-100%. So we took to the dark and deserted highway, too early for anyone to be on it, leaving Pennsylvania to enter Ohio.

Two hours and tens of miles later we had reached Mount Vernon, OH a small University town with a population of just a few thousand, but still the largest area for miles around. We found a charming little café where we regrouped with coffee and bagels.

Despite all our hopes of clearer skies out West, we were pretty much in the same situation we had started in. The clouds covered everything for hours around us, the closest area without major cloud coverage was another 2 hours west in Indiana. Driving two hours might not seem bad, but what we drove out we would have to drive back, meaning a four hour drive back to Pittsburgh that evening. However, we hadn’t come this far for nothing, and we decided to continue on, GPS set for Indiana.

As we drove on, the skies got optimistically brighter and the clouds scarcer, until at around 1pm we rolled into Richmond, Indiana, a tiny town that felt strikingly deserted. As we drove through to find a place to watch the eclipse, we passed schools entirely empty, mall parking lots without any cars, and sidewalks deserted. It felt like a ghost town, but soon enough we pulled into a public park and found exactly where everyone was. Sprawled across a giant lawn were hundreds of picnic blankets, lawn chairs, and telescopes. The entire population of Richmond and many tourists like us had all gathered in this one park.

So we set up camp—many blankets, many chairs—and, equipped with solar eclipse glasses, set our eyes on the sun. In the voidless black world which our glasses created, the sun was slowly being eaten: first it was a cookie with a nibble in it, then a packman, then a banana then barely more than a sliver. Of course, the whole experience took at least an hour, and by the time the sun was down to a sliver there was a haze around us, the world was tinted in warm light—a mid day golden hour. At 3:06 we all put on our glasses again and watched the last of the sun be swallowed by the moon; the sliver became a dot and the dot became darkness. An eerie quiet settled on the field as we all took down our glasses and stared at the sky: a steely dark blue with a 360 degree pink glow floating on the horizon, the sun reduced to an ominous halo in its depth. For nearly four minutes the sun was slain. The street lights turned on and the world shifted at least 5 degrees colder. It was cosmic—apocalyptic even. It was sublime.

In that moment, not only did the natural world fall quiet, but so too did all of the people around us. Hundereds all in the same place, but for a few precious moments, no one made a noise. It was breathtaking to behold, and so far from the normal that even though we knew what to expect, seeing it in reality sort of shocks you. Eventually cheers started up breaking the silence as the moon slipped away, letting the light and warmth back into the world.

Even as the eclipse ended, and we were faced with a daunting 5 hour drive back to Pittsburgh that afternoon and a 4 hour drive back home the next morning, we felt accomplished. Even though it was only for a few minutes, the total solar eclipse was worth those hours of driving. Eclipses are rare. They don’t occur on every planet. We are so lucky to have our moon at the right distance to the sun for this to occur. Even more lucky, to have the two align over our country. And luckier still to be there, to be alive under it all.